I’ve been reading Jane Allison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode—her craft book about narrative patterns beyond the classic arc—and I love that trio of dictums as writing advice too. There is no right way to write. There is no template routine or habit. In fact, I like the idea that most of what works for most of us is to meander: to trail away from our current habits when we’re stuck and try something that (for us) we don’t normally do.

What I mean is: what kind of writer are you most of the time?

Take inventory and then—subvert.

take INVENTORY

Do you typically write at day or night?

On weekdays or weekends?

Do you write every day?

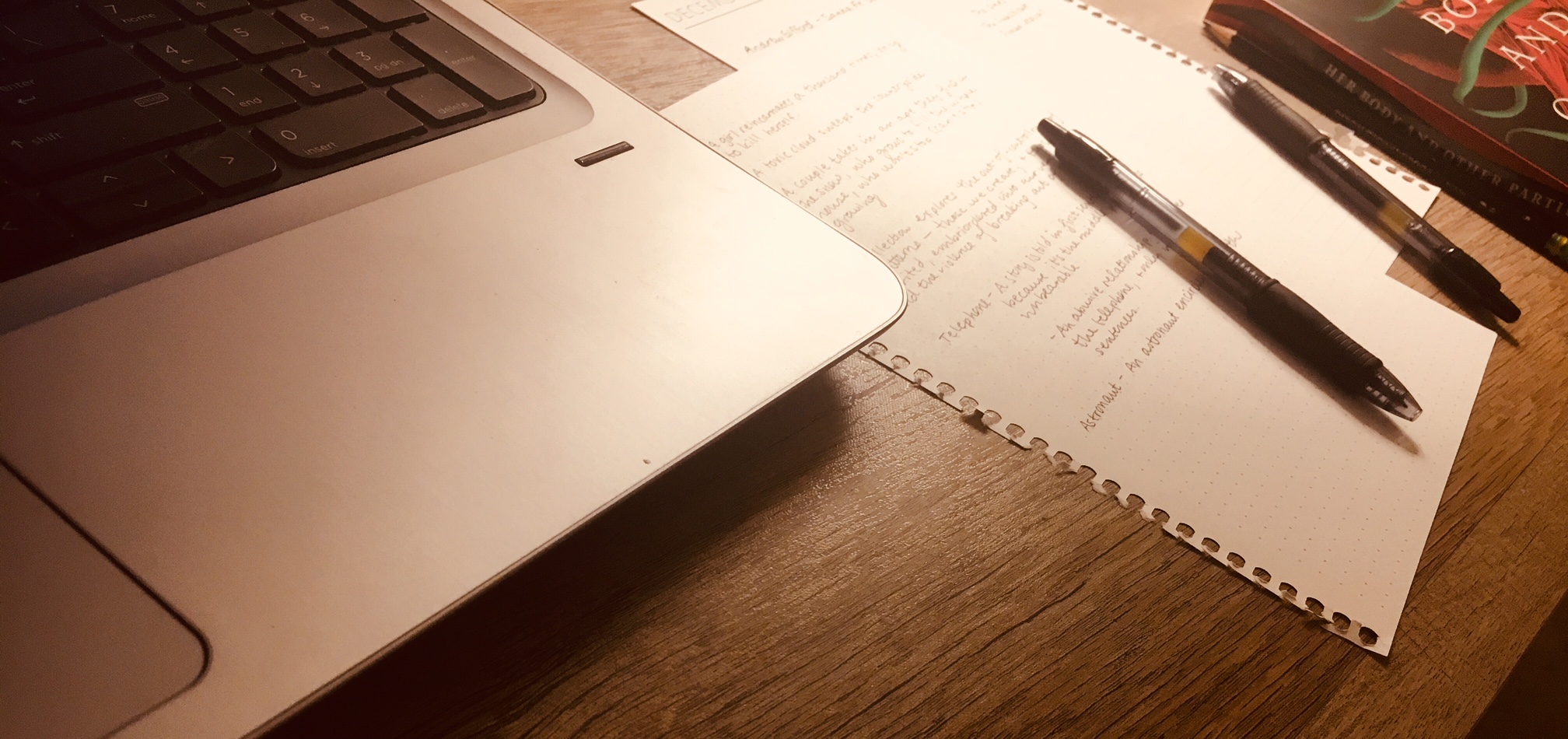

Do you write longhand or type?

Do you have designated writing hours or steal time when you can?

Do you revise and polish one paragraph at a time, or do you write a fast, rough, complete draft?

Whatever your usual habits are—that’s your baseline. That’s what works FOR YOU. Or, what usually works for you.

But even what usually works will sometimes fall flat. When you feel just stuck.

So—shake things up.

INVERT

This one’s my go-to change-of-pace: whatever I usually do, I invert.

Let’s say, for my baseline, I’m this kind of writer:

I type my stories

Usually in the afternoon

Usually for as long as I feel like it

Usually picking up where I left off

Usually pruning and polishing my writing as I go

So….to shake things up, I’ll:

Write longhand

At midnight

For a timed 20 minutes

Starting a brand new story

Without crossing out a single word

Now, you might not have the ability to invert every habit. That’s fine! But switch up one or more significant habits. Writing longhand, I find I produce really different work than drafts I type. I’m a different writer on a clock than untimed. I’m a different writer at different times of the day. I’m different when I’m angry, when I’m hungry, when I’m tired. I’m a different writer when I smooth out each sentence in a paragraph before moving on versus the writer deep in the havoc of a messy first draft.

COSPLAY

In her craft capsule essay, The Schedule, Jordan Kisner calls it “cosplaying the work”—her attempt at building regimented schedules, habits, routines. She writes, “I’ve never managed it. I work in spurts, at random hours, crashing deadlines and taking ill-advised breaks and wasting just so much time. And of course there is no right way to have a writing schedule; of course brilliant writers have written at all hours and according to all manner of quirky or mundane habits; of course the only thing anyone cares about in the end is whether you wrote and whether it’s any good.”

So many of us are this way! And yet—we want it to be as simple as a militaristic writing schedule, as the 5 AM writers club, showing up every day, waiting for the muse to show up too.

But it just…doesn’t…work for us.

Often trying to imitate these really rigid daily schedules ends in failure and a sense that we’re some kind of imposters. We weren’t productive. We have so little to show for those hours with our ass in the chair.

But—I like Kisner’s idea of ‘cosplay.’

What it we—only temporarily—put on the costume of the kind of writer who gets up at dawn and writes for an hour? What if we did this for one week only? Or only a day? What if sometimes we just play act what works for other writers to see if it works (for a short while) for us?

For example you could:

Rent a hotel room and write every morning at six-thirty (Maya Angelou)

Write all night (Kafka)

Write laying down all day (Capote)

Write standing up (Virginia Woolf)

Write outside, in the countryside, preferably while looking at a cow (Gertrude Stein)

Kisner has many more examples in her essay, and also points to Daily Routines if the cosplays above aren’t adventurous enough for you.

JILT

Okay this last one sounds wild—jilt. To cheat. To desert. To abandon. I don’t mean forever, but I do mean—don’t. Don’t write for a little while. Cheat on your writing with other creative stuff instead.

Paint.

Throw clay.

Sculpt.

Cook.

Bake.

Make a podcast (ugh).

Play the guitar, the piano.

Sing.

Make a powerpoint.

Make a cocktail.

Make a meme.

Do new kinds of art badly and happily.

What I mean is take time off from the art that you’re best at. Unlimited time off! Because sometimes you just need it. Because sometimes it’s hardest to do the thing you’re best at badly.

But it’s easy—EASY!—to do art you’re not the best at badly.

It’s easier to not be hard on yourself, too.

Take time to paint a flowerpot or something—something you don’t really know how to do—just to remind yourself that all art starts as mess-making. As amatuering. Take joy in that mess.

When you come back to your writing, don’t be afraid to take that mess-making instinct with you. To allow in glee, experimentation, disaster. Have compassion for that person who sometimes looks at the blank page like they’ve never seen one before.

HIATUS

This is an extension of jilt: because jilt, while a fun word, implies cheating. Like, writing is your spouse and you had an affair with acrylic paints.

But seriously, writing is not your spouse. Writing is more an extension of the self than an entity outside it.

And I guess what I’m arguing is—you can’t cheat on yourself.

And sometimes you need gentle permission to take a long, long, long break. That’s hiatus. Even the word—sounds soft.

Sometimes you, a writer, need expanses of time (months…years…) to not write. You need to breathe. You have life stuff. You are good-busy or bad-busy. You deserve a chance to recharge without some sense of ‘why haven’t you written anything lately’ looming overhead.

You are human, and you need rest.

But you can still shake up how you rest. The same way you might produce really different writing if you invert your routine, you can also recharge really differently depending on how you hiatus. So first, take stock.

INVENTORY

When resting, do you tend to tune in or tune out?

Do you usually rest at home or vacation elsewhere?

Do you rest with your phone/device or ‘unplugged’?

Do you recharge alone or with others?

Do you recharge indoors or outdoors?

What foods or drinks recharge you?

How do you want to feel at the end of rest? What does “recharged” feel like to you?

Just like with writing habits, there are no better or worse ways to rest. What habitually works for you works for a reason—it probably means it’s working. But it also might only be habitual—easy or accessible. Consider what an inversion of your resting habits looks like.

For me, I typically rest at home, indoors, goofing on my phone. That’s what usual, daily rest looks like for me. But: sometimes I surprise myself.

I take a nap in the hammock.

I read at a cafe.

I take myself out to dinner.

I take a midnight swim and float under the stars.

As an introvert I often (but not always) recharge alone. But one of my favorite (surprising!) ways to recharge was to read in the same room as a friend for an afternoon. I had company. We were reading different books and each sunk into our own couch. One of us might laugh or smile. We each dozed off at different times.

An extrovert might have a really different way of recharging. An extrovert might look at my list and see it as (quietly) adventurous, just as I might considering long nights dancing, backyard BBQs, chatting with strangers, karaoke.

What I’ve learned is that I recharge most differently when I am intentional. When I “take myself out”—treating a hiatus as a date or special treat, rather than an ‘escape.’ This is why I feel very different after hiking for an hour than scrolling Twitter for an hour. One helps me tune in (gently), one helps me tune out.

I feel different singing, windows-down-in-the-car than afternoons floating in a pool. I feel different browsing Bookmans than sipping lavender lemonade. I get different degrees and kinds of joy.

I am glad for all of them.